La Fille Mal Gardée is often translated as “The Poorly Guarded Daughter” or “The Unchaperoned Daughter.” Along with “The Whims of Cupid and the Ballet Master” (1786, by Vincenzo Galeotti), it is one of the few surviving 18th-century ballets, although in a very different form from its original premiere in 1789. Choreographed by Jean Dauberval in 1789, it was one of the first ballets to abandon mythological themes in favour of characters who could have existed in real life. So, the protagonists are ordinary peasants. It was also one of the first comic ballets.

Over the course of two centuries, it has been revived in numerous versions with varied choreography and scores, including music by Ferdinand Hérold, Peter Ludwig Hertel, and others. In this article, we’ll tell you about its origins, plot, and most popular versions.

Table of Contents

The Plot of La Fille Mal Gardée

ACT I

Scene 1: The farm.

Lise, the only daughter of the widowed Simone, a prosperous farmer, is in love with Colas, a young farmer. However, her mother wants Lise to marry the foolish but extremely wealthy Alain and has arranged (with Alain’s father, Thomas) a marriage contract between Lise and Alain.

At dawn, the farmhands go out to work, and a rooster and some hens awaken to the new day. Lise begins her work, but her thoughts are on Colas: she leaves a ribbon as a token of her love, and when Colas enters, he finds it.

The lovers’ meeting is interrupted by Simone, who chases Colas away and puts her daughter to work churning butter. The lovers manage to find a way to meet and express their devotion, but soon the farm women enter, and Lise dances with them. Simone sends her farmhands out into the fields, and Lise tries to escape with them.

Just as her mother is telling her off, Thomas, a prosperous vineyard owner, enters with his naive son Alain, who is destined to be Lise’s husband.

Lise is not at all impressed by Alain’s antics, but she and her mother accompany Thomas and Alain to the harvest field.

Scene 2: The cornfield.

The reapers have finished their work, and Colas leads them in a lively dance. When Lise arrives with Alain and her parents, she manages to escape with Colas, while the reapers mock Alain. Lise and Colas express their love in a pas de deux.

When Simone discovers this, she is furious, but they persuade her to show off her skill with a clog dance. But just then, a storm breaks out, and everyone runs for shelter.

ACT II

Scene 1: Inside Simone’s farmhouse.

Mother and daughter return soaked to the bone. They sit down to work, but Simone falls asleep, and Lise manages to dance with Colas in front of the closed kitchen door. The workers bring in sheaves of grain from the fields, after which Simone goes out to arrange the signing of the marriage contract. While alone, Lise talks to herself about the delights of marriage and motherhood. Suddenly, Colas emerges from his hiding place under the stacked sheaves. They declare their love for each other once more, until Simone suddenly returns.

Desperate, Lise sends Colas to hide in her bedroom. Simone rushes in, suspicious of Lise’s behavior. The widow is certain that Lise has been seeing Colas, but she can’t prove anything. Widow Simone orders Lise to go to her room and put on her wedding dress for her upcoming wedding to Alain. Horrified, Lise tries to stay put, but Widow Simone pushes Lise into her room and closes the door.

Thomas and Alain then arrive with the village notary, and the marriage contract is signed. The farm workers (friends of Lise and Colas) also arrive. The widow Simone gives Alain the key to Lise’s room. After receiving the key to Lise’s bedroom, Alain is instructed to go and claim his prize. When Alain opens the door to Lise’s room, she appears in her wedding dress, accompanied by Colas.

Thomas and Alain are offended, and Thomas, enraged, tears up the marriage contract. Thomas, Alain, and the notary leave the house in anger. Lise and Colas then beg the widow Simone to approve of their love. Simone relents, blesses the happy couple, and the ballet ends with a dance of general rejoicing.

The Origins of La Fille mal gardée

Where did the idea for this ballet come from? Some dance historians have suggested two possible sources. On the one hand, the comic opera La Fille mal gardée (1758) by the Italian composer Egidio Romualdo Duni (1708–1775). On the other hand, an 18th-century engraving of a mother telling off her dishevelled son. However, the British historian Ivor Guest has questioned the likelihood of a connection with Duni, since Duni’s music is not used in the ballet. Besides, Duni’s story differs from Dauberval’s. Today, we also cannot know what influence the engraving may have had.

Dauberval’s innovation solved a key challenge for 18th-century choreographers: seamlessly integrating dance into the narrative.

By choosing a “danceable” story, he ensured that removing any dance sequence would render the work meaningless. This seamless fusion, where dance is indispensable to understanding the story, is the secret of its enduring success.

The Influence of Commedia dell’Arte on La Fille Mal Gardée

Whatever the immediate source of inspiration, the basic plot outline on which the ballet was based was commonly used for theatrical works of all kinds during Dauberval’s time. Two young lovers have their marriage plans ruined by the young woman’s father, who has another candidate in mind. Then, at the end of the story, true love triumphs over authority, and everyone lives happily ever after. The characters in Fille also come from a common source: the commedia dell’arte. Lise and Colas are the young lovers; Alain, the clown or “zanny”; and Mother Simone, the “pantaloon.”

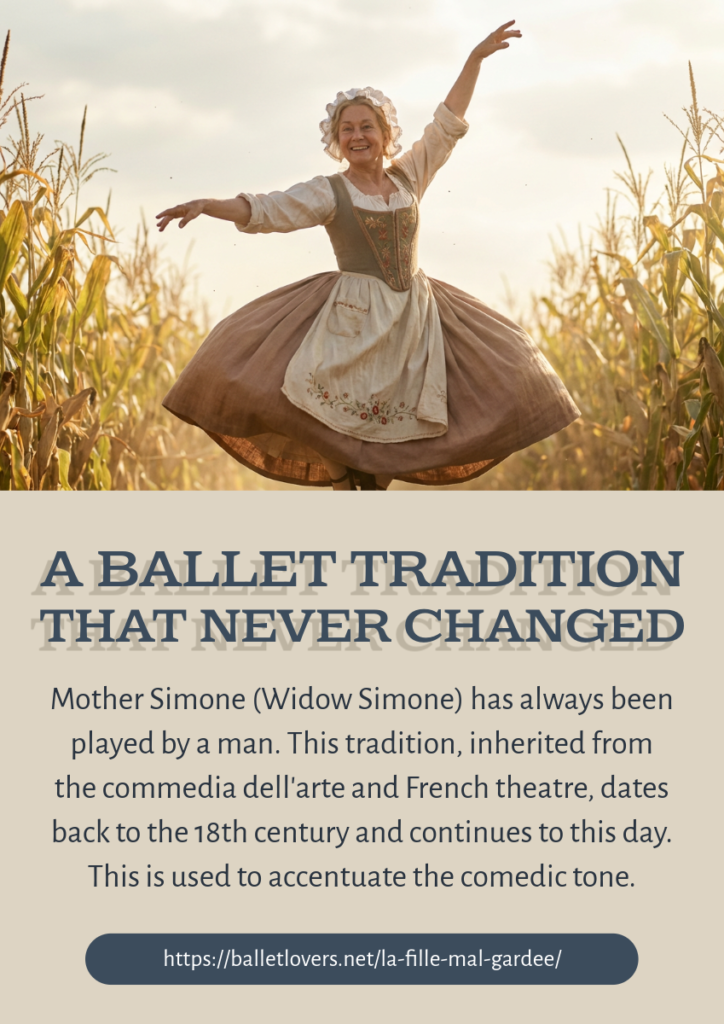

On the other hand, the character of Mother Simone (Widow Simone) has always been played by a man. This tradition, inherited from the commedia dell’arte and French theatre, dates back to

the 18th century and continues to this day. This is used to accentuate the comedic tone. A male dancer portraying a clumsy peasant mother creates an immediate humorous effect, especially in scenes like his fights with Lise and the famous “Clog Dance.” It’s worth remembering that La fille mal gardée is a comedy.

You Might Also Like ✨

The Premiere of La Fille Mal Gardée

- Choreography: Jean Dauberval.

- Ballet in three scenes.

- Music: various composers— later Peter Ludwig Hertel .

- First performance: 1 July 1789, Grand Theatre, Bordeaux.

- Principals: Mademoiselle Theodore (Lise) and Eugene Hus (Colas).

La Fille mal Gardée premiered on July 1, 1789, at the Grand Théâtre de Bordeaux, with choreography and libretto by Jean Dauberval. It was first titled Le Ballet de la paille, ou Il n’est qu’un pas du mal au bien (The Ballet of Straw, or There is only one step from bad to good). The musical score consisted of a selection of compositions by various authors, including Franz Joseph Haydn. The first Lise and Colas are unknown, although it is likely that Lise was played by Mademoiselle Theodore (Dauberval’s wife) and Colas by Eugène Hus, one of the most popular dancers of the time. A certain Monsieur Brocard was the first Mother Simone (originally called Bagotte, a popular stage name).

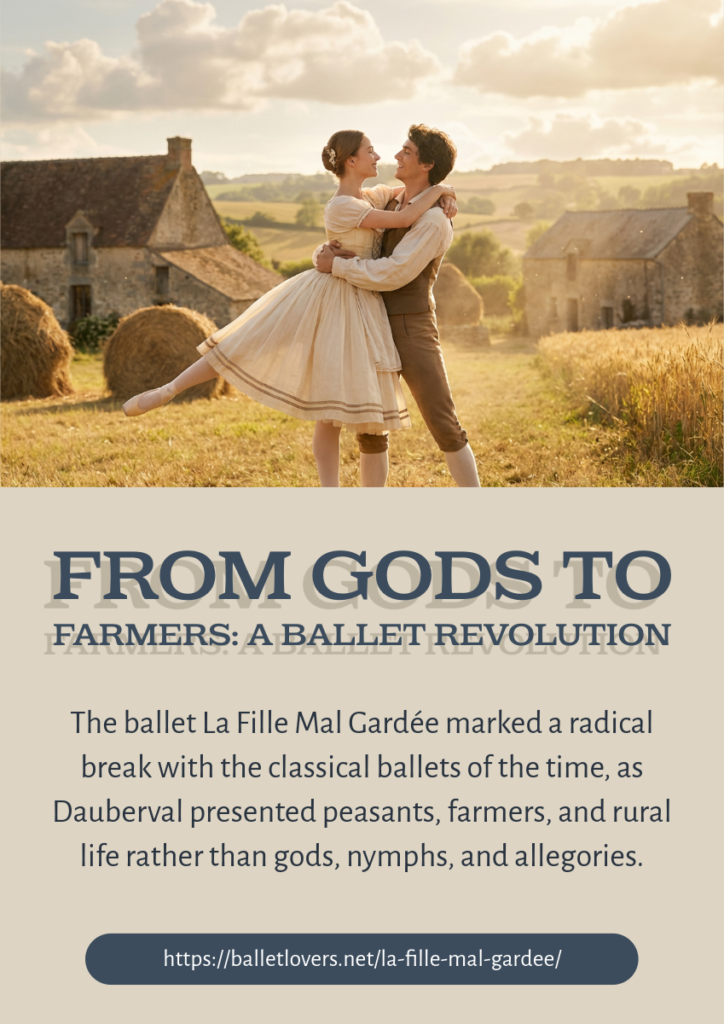

The ballet marked a radical break with the classical ballets of the time, as Dauberval

presented peasants, farmers, and rural life rather than gods, nymphs, and allegories. In this way, the choreographer followed the dramatic principles of his teacher Jean-Georges Noverre, who advocated for truthful observation and ballet of action: a dance driven by story rather than decorative display.

On the other hand, the success of La Fille Mal Gardée could not have come at a better time for Dauberval, who needed to rebuild his professional reputation. He was coming off a resounding failure with Dorothée (1788) and was in the midst of a perfect storm: financial disputes with the theatre management and a bitter personal conflict with the dancer Chevalier Peicam.

Later European and American Versions

Following its success in Bordeaux, the ballet had numerous productions throughout Europe. In 1791, it premiered in London, where it acquired its current title, La Fille mal gardée, with Mademoiselle Théodore reprising her role as Lise and Charles-Louis Didelot as Colas. Critics praised the pantomime, especially the scene with the spinning wheel and tambourine.

Revivals in London continued well into the 19th century:

- James Harvey D’Egville’s productions at the King’s Theatre (1799, 1800, 1802, 1815)

- Royalty Theatre (1802, titled Honi Soit qui Mal y Pense)

- Olympic Pavilion (1808)T

- Surrey Theatre (1825)

- Adelphi Theatre (1826).

Paris first saw the ballet in 1803 at the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin in a production by Eugène Hus, where Madame Queriau created a celebrated Lise, admired for her dramatic portrayal of fear and love. The official premiere at the Paris Opera took place in 1828, under the direction of Jean-Louis Aumer and with a new score by Ferdinand Hérold. The cast included Marinette Launer as Colas and Pauline Montessu as Lise, with later appearances by the iconic Marie Taglioni (1804–1884) and the virtuoso August Bournonville (1805–1879). It remained in repertoire until 1854, with a dramatic performance by the sensual Austrian dancer Fanny Elssler (1810–1884) in 1837.

Other European performances included those by Salvatore Vigano in Venice (1792); Lanchlin Duquesnay in Naples (1797); Marseille and Lyon in the 1790s; and Giuseppe Salamoni in Moscow (1800). In the United States, it may have premiered before 1800 in Philadelphia, with a confirmed performance in New York in 1828. Fanny Elssler danced Lise at her American farewell on July 1, 1842.

Russian Versions

Russia became a stronghold for ballet. La Fille Mal Gardée premiered in St. Petersburg in 1818 and was revived by Didelot in 1827. Famous ballerinas such as Fanny Elssler and Avdotia Istomina helped maintain its popularity.

A crucial milestone occurred in 1885, when Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov presented a new version in St. Petersburg, with the music composed by Peter Ludwig Hertel in 1864 for a Berlin production by Paul Taglioni. This version starred Virginia Zucchi and served as the basis for many subsequent productions, including those by Alexander Gorsky (1901) and Leonid Lavrovsky (1937).

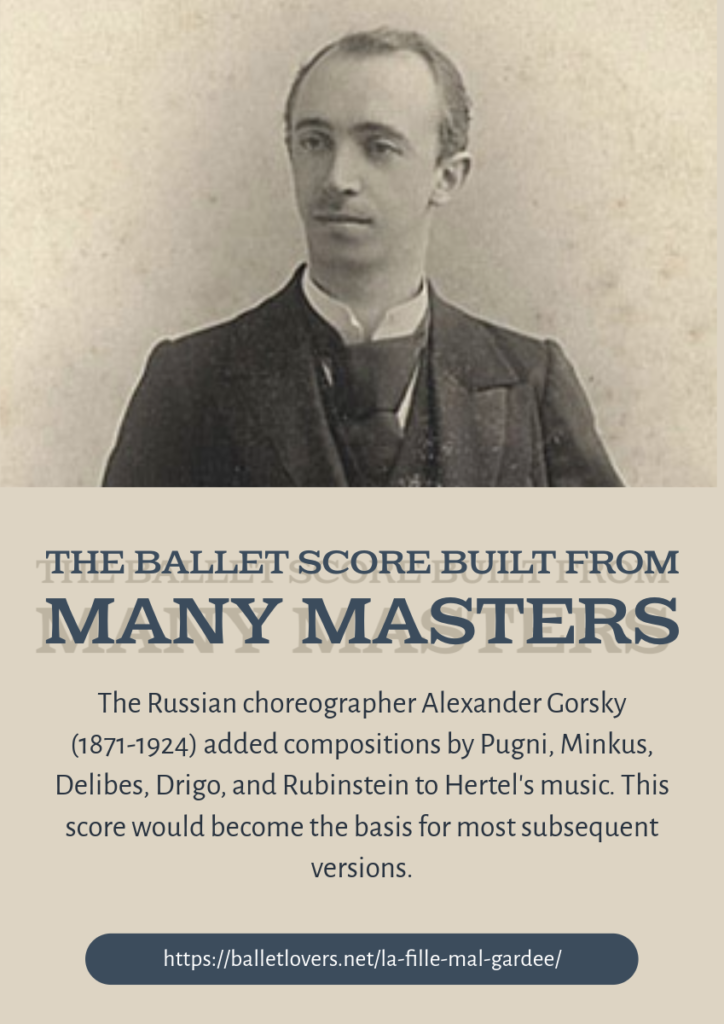

Gorsky added compositions by Pugni, Minkus, Delibes, Drigo, and Rubinstein to Hertel’s music. This score would become

the basis for most subsequent versions. Notable Lises included Matilda Kschessinska, Olga Preobrajenska, Vera Trefilova, Tamara Karsavina, and Marina Semenova.

20th-Century Versions

Western productions of the 20th century often followed Russian traditions. Anna Pavlova danced an abridged version in London (1912). Alexandra Balashova performed it in Paris (1922). Mikhail Mordkin presented it in Flint, Michigan (1937) and revived it for the Mordkin Ballet of New York (1938) with Lucia Chase as Lise. Bronislava Nijinska revised it for Ballet Theatre (now American Ballet Theatre) in 1940, retitling it The Wayward Daughter (1941) and Naughty Lisette (1942), with Irina Baronova and Dimitri Romanoff. Romanoff revived it in 1949, with Nana Gollner and Igor Youskevitch. Fernand Nault created versions for the American Ballet Centre (1960) and the Robert Joffrey Ballet. Alicia Alonso staged a version based on Nijinska for the Alicia Alonso Ballet (1952) and the National Ballet of Cuba (1959).

Other notable productions include:

- The National Ballet of Canada (1976, Ashton’s version with Karen Kain and Frank Augustyn);

- Heinz Spoerli at the Paris Opera (1981), subsequently in Basel, Helsinki, Düsseldorf, Oslo, Milan, and Hong Kong;

- The Joffrey Ballet (1986)

- Houston Ballet (1992).

- In Russia, Sergei Vikharev used the Sergeyev Collection notation for the Ekaterinburg State Ballet (2015).

Ashton’s version of La Fille Mal Gardee

- Ballet in two acts.

- Choreography: Frederick Ashton. Music by Ferdinand Herold, freely adapted and arranged by John Lanchbery.

- Scenery and costumes by Osbert Lancaster.

- First performed by Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, 28 January 1960.

- Principal Dancers: Nadia Nerina: Lise. David Blair: Colas. Stanley Holden: Widow Simone. Alexander Grant: Alain. Leslie Edwards: Thomas.

- First presented in the United States by the Royal Ballet at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, September 14, 1960, with the same principals.

The work of British choreographer Frederick Ashton (1904-1988) is a complete reworking of the old ballet. The music was an arrangement by John Lanchbery based on Ferdinand Herold’s 1828 score, as discovered by ballet historian Ivor Guest. Only the story and, to some extent, Herold’s music and a few mime scenes are retained. Undoubtedly, this is one of the most popular and successful versions, premiering on January 28, 1960, in London with Nadia Nerina as Lise and David Blair as Colas. Ashton’s La Fille Mal Gardée is also the first British ballet to use English folk dance as source material. For example, the Maypole Dance in Act I and the famous clog dance performed by Mother Simone.

So, in an interview, Frederick Ashton observed that La Fille Mal Gardée is a truly English work. “It has the Lancashire clog dance which is almost like a folk dance. Fille came about in a very odd way because of Karsavina (Tamara Karsavina, famous Russian Dancer). She was always after me to do it. I didn’t particularly like the idea and I didn’t like the music to the traditional version, by Hertel. I went back to Herold, who did it originally… It was mostly a matter of selecting and curtailing. I always work out the structure of a ballet before I start—who’s doing what and for how long. I don’t do any steps until I’m with the dancers. The structure for Fille I worked out with John Lanchbery, marking the music.”

Critical Reception of Ashton’s Version

Andrew Porter, music and dance critic of The Financial Times, London, has said of this ballet: “The first act, in two parts, lasts just over an hour; the second, thirty-six minutes. There is not an ounce of padding. Invention tumbles on invention, and the whole thing is fully realised in dance. (…) The choreography is wonderfully fresh, and the shape of the scenes is beautifully balanced.”

Also, the British dance critic David Vaughan has written in Ballet Review magazine about Ashton and this ballet:

“He is a great comic choreographer. La Fille Mal Gardee is a perfect expression of his artistic benevolence. (…) Each set of characters has its distinct style. The young lovers dance in a now playful, now softly melting classicism. The farmers’ choreography combines classicism with folk dance borrowings to suggest the union of man with nature and a love of meaningful work. Simone, Thomas, and Alain derive from farce, pantomime, and music-hall. The dancing chickens, which some balletgoers find annoyingly “unrealistic,’” may be there to be deliberately artificial, to emphasize right from the start that this ballet, however homely its subject, is not photographic naturalism, but instead uses the exaggerations of comedy to point to certain human truths.”

Conclusion

Ashton’s work was a resounding success from the moment it premiered. Some of the highlights were the Nerina and Blair variations and the eccentric Chicken Dance in Act I. The construction of the ballet was masterful, blending dance with care and narrated with a magnificent sense of humor. Ashton succeeded in creating an unparalleled comedic masterpiece without ever sacrificing dramatic development. The choreographer wrote the ballet for two outstanding virtuoso dancers, Nerina and Blair, showcasing their skill with dazzling inventions. Also, the ballet celebrates the quality and achievements of the traditional English school. Finally, the ballet also became a success in productions by Australian and Canadian national companies.

Buy your tickets for La Fille Mal Gardee 2026

Royal Opera House

23 May–9 June 2026

BookBibliography

- Brinson, Peter. Ballet and Dance: A Guide to the Repertory.

- Terry, Walter. Ballet Guide: Background, Listings, Credits, and Descriptions of More Than Five Hundred of the World’s Major Ballets.

- International Encyclopedia of Dance. A project of Dance Perspectives Foundation, Inc.

- Chujoy, Anatole. The Dance Encyclopedia.

- Balanchine, George, and Francis Mason. Balanchine’s Complete Stories of the Great Ballets.

Leave a Reply