The term “character dance” is often confusing, even for ballet experts. Sometimes it can refer to folk-inspired dances, such as Hungarian or Spanish ones. But at other times, it describes roles such as princes, peasants, or comic figures in classical ballets. This ambiguity is not accidental: it reflects the historical evolution of ballet. In this article, we will attempt to clear up this confusion and explain the fascinating evolution from the hierarchies of Louis XIV’s France to Petipa’s divertissements.

Table of Contents

The Three Genres of the French School

In the 18th century, French ballet classified dancers according to their physical and artistic characteristics. These categories, called “genres,” determined which roles each dancer could perform. They also reflected social hierarchies. These classifications were not merely dance styles but systems that shaped training, casting, and the very structure of performances. Despite some teachers’ attempts to preserve the genres, they disappeared definitively around 1830. Below, we explain the three existing genres:

Noble/Sérieux Dancers (Noble Genre)

Dancers in this category were tall, with perfectly proportioned figures, well-formed legs, well-formed insteps, and flexibility in their hips. This genre was considered the most difficult, requiring the utmost precision in the adagios, considered the cornerstone of the art of dance.

The movements were sober, dignified, and symmetrical, designed to express authority, harmony, and moral virtue. It emphasised poise, batteryie (a type of rhythmic footwork), and aristocratic bearing, with solemn elegance in the movements and grace in the attitudes and arabesques. By the 1820s, noble dancers were also performing feats such as second-position pirouettes, attitude, entrechats, and other jumps.

The noble genre was very elegant. So, it was reserved for figures of high social standing, such as kings, princes, gods, and heroic figures. In this way, the genre established the physical language that would later be associated with high-status classical roles. A clear example is Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake.

Demi-Caractère (Semi-character)

These dancers were typically of medium height and slender build. Their style was a technical blend, combining the elegance of the noble genre with more fluid, athletic movements. The demi-character dancer was usually shorter than the noble dancer but possessed all the technical virtuosity of a leading artist. In other words, the demi-character occupied a middle ground between noble and comic roles. These characters were often pastoral figures, villagers, or supporting characters.

The movement was livelier and more expressive than that of the noble dance, yet it remained technically refined. This genre allowed for individuality and emotional nuance without descending into caricature.

A demi-character dance was performed with steps based on classical ballet technique, often for roles that demanded both acting and technique. A famous example of a demi-character dancer is the Bluebird in Sleeping Beauty.

The Comique (or Character) Genre

These dancers were short in stature and stocky. They were the original performers of folk and national dances. So, comic dance was reserved for exaggerated, humorous, or grotesque characters. It relied on strong theatricality, mime, and physical distortion, rather than classical purity. Although less prestigious, comic dance played a crucial role in storytelling and audience interaction.

They performed national dances such as the bolero, the tarantella, and the allemande. It was considered the least important genre, but it included folk and national elements that provided contrast. A typical example is the Widow Simone (Mother Simone) from the ballet La Fille Mal Gardée. Often played by a man who uses comic tricks (such as fainting or primping), this is a classic character rooted in the commedia dell’arte tradition.

Romantic Ballet and the Birth of Modern Character Dance

During the 19th century, Romanticism emerged, emphasising emotion, exoticism, and nationalism. With the “Taglionization” of ballet (the rise of the famous dancer Marie Taglioni), the art form’s structure changed, leading to the disappearance of the three distinct genres around 1830. The noble and the comic faded away, giving way to the dominant semi-character dance, as the public rejected everything associated with the old monarchical regime.

The term “character dancing” usually refers to an ethnic dance adapted for use in ballet. It generally refers to folk and national dances. Regarding costumes, character dances are not usually performed en pointe, and the dancers may wear ethnic costumes, headdresses, and footwear. In a ballet, character dancing provides local colour, helps to set the scene, and can add variety to a divertissement. A typical example is the ethnic dances in Swan Lake (Spanish, Neapolitan, Polish, and Hungarian). Also, the ballet score may incorporate musical characteristics of the dance type.

Romantic ballet experienced a boom in character dancing. In 1830, Spanish dance became fashionable, boosted by the success of Fanny Elssler in Le Diable Boiteux (1836). Choreographers such as Marius Petipa adapted folk dances to academic ballet, superimposing ethnic arm and torso movements onto classical legwork. His well-known character dances appear in Don Quixote (1869), La Bayadère (1877), Raymonda (1898), The Nutcracker (1892), and Swan Lake (1895). These dances brought colour contrast and variety to the divertissements, such as the ethnic dances in the ballroom of Swan Lake (Spanish, Neapolitan, Polish, and Hungarian).

You Might Also Like ✨

When the Male Dancer Lost His Central Role

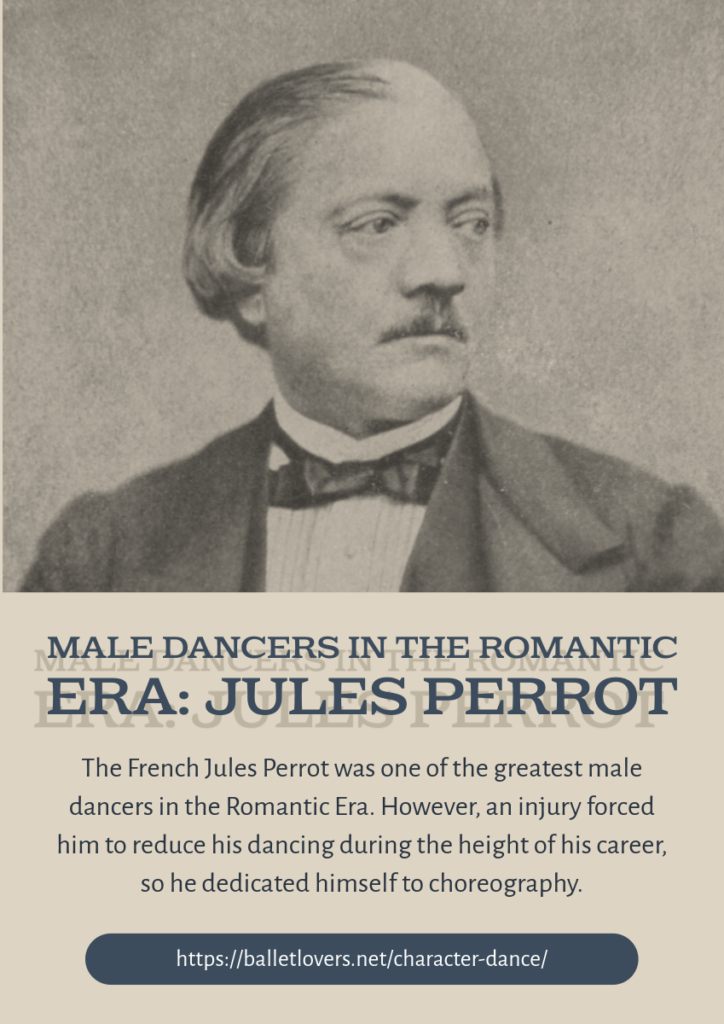

On the other hand, the disappearance of the noble genre, in which the male dancer was particularly prominent, foreshadowed the declining importance of men in ballet. So, in the Romantic Era of Ballet, France produced only one great male dancer capable of competing with the ballerinas on equal terms: Jules Perrot.

However, an injury forced him to reduce his dancing during the height of his career, so he dedicated himself to choreography. In fact, several highly talented male dancers performed in Paris: Lucien Petipa, Marius Petipa’s older brother, Antonio Guerra, and August Bournonville.

However, over time, the male contribution to ballet was reduced to performing male roles and, in the dance itself, to modestly supporting the ballerina.

By the 1840s, such a strong aversion to male dancers had taken hold that they were excluded from the corps de ballet whenever an excuse arose. It was in this context that the allure of the cross-dressing dancer emerged in the 1860s and 1870s. This undoubtedly affected the level of male dancers, as fewer men pursued dance professionally, and those who did lacked the encouragement to push themselves further. In 1847, there were only twelve boys among the ninety students at the Opera’s School of Dance.

Character Dance Today: Definition, Technique, and Examples

It is essential to distinguish between these two related but different concepts: Character Dance” vs. “Dances of Character”

Character Dance

This refers to the technical style derived from traditional, national, or ethnic sources (such as a Czardas or a Mazurka). That is, it refers to national, folk, ethnic, and rustic dances adapted for ballet. These are not authentic reproductions, but rather dances adapted for theatrical purposes: they add local colour, set the scene, contrast with classical ballet, or present varied entertainments. They adopt distinctive characteristics such as steps, gestures, body posture, formations, and dynamics, sometimes to create stereotypes (for example, the hand behind the head in “Slavic” dances and the undulating arms in “Indian” dances). They are performed without pointe shoes, often in heeled shoes, boots, or ethnic footwear, and with full skirts for women.

The most popular styles include:

- Scottish (Bournonville’s La Sylphide, Coppélia’s Swanhilda);

- Italian (Bournonville’s Neapolitan tarantella, Petipa’s Neapolitan in Swan Lake);

- Spanish (head held high, back arched, arms in a fourth/fifth position: Petipa’s Don Quixote pas de deux, Kitri’s fan, Basil’s footwork).

- Other styles include Hungarian, Oriental, nautical and military.

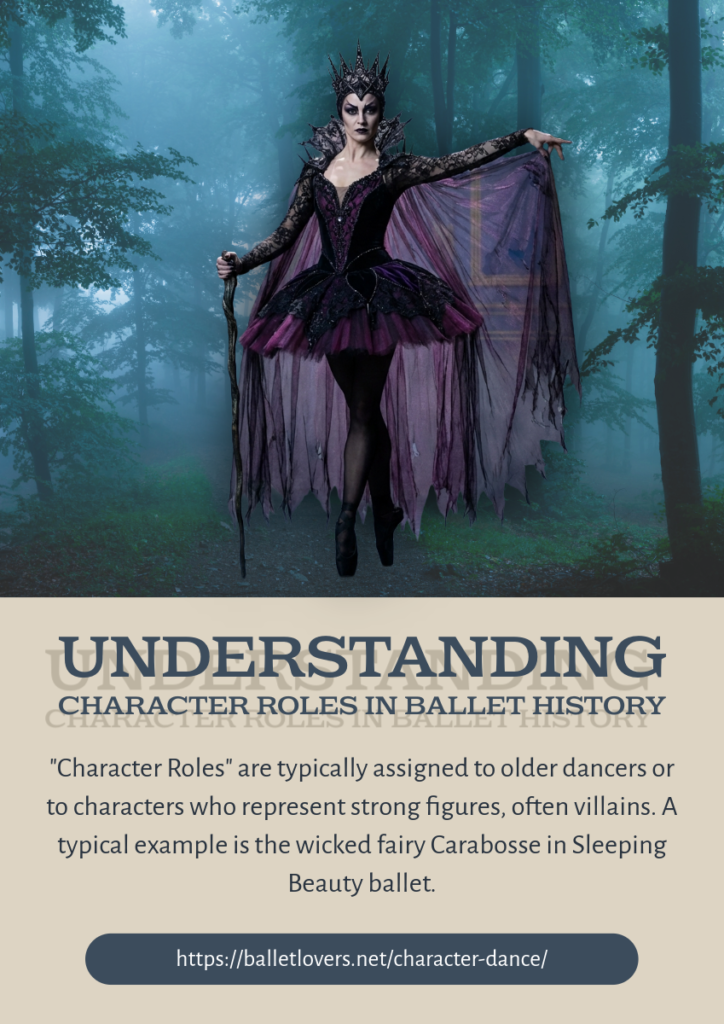

Dances of Character (Character Roles)

These are roles that suggest personality traits, social status, or individual occupations, rather than ethnic identity. They are usually roles for older dancers or for characters who represent strong figures, often villains. For example:

- Alain and the widow Simone in La Fille Mal Gardée (1789)

- Madge in La Sylphide (1832), Dr Coppelius in Coppélia (1870),

- Carabosse in Sleeping Beauty (1890)

- Drosselmeyer in The Nutcracker (1892)

- Von Rothbart in Swan Lake

- Gamache in Don Quixote.

- Don Quixote in Don Quixote Ballet.

Conclusion

Although modern ballet no longer uses the strict French terminology of the genre, its logic remains deeply rooted in the classical repertoire. For example, when we speak today of “noble characters” (such as princes or heroes), common people, or comic roles, we are still drawing on the same expressive hierarchy established in the earliest ballets.

Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake, for instance, embodies the legacy of noble dance. At the same time, secondary characters or ensemble dances often reflect semi-character qualities, while comic figures retain the theatrical exaggeration of comic dance.

Bibliography / Sources Consulted

- International Encyclopedia of Dance. New York: Oxford University Press, Dance Perspectives Foundation, Inc.

- Guest, Ivor Forbes. The Romantic Ballet in Paris. London: Pitman, 1966.

- Craine, Debra, and Judith Mackrell. The Oxford Dictionary of Dance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Chujoy, Anatole. The Dance Encyclopedia. New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1949.

- Lawson, Joan. A Ballet-Maker’s Handbook: Sources, Vocabulary, Styles. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1976.

Leave a Reply