What was the Premiere of The Nutcracker Ballet like? How was this famous ballet created? The Nutcracker premiered on December 18, 1892, at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg. Although it didn’t initially receive the best reviews, over the years, it has captured the hearts of millions of people worldwide. In this article, we’ll tell you all about the creation of this ballet and some interesting facts about its beautiful music.

Table of Contents

The Context That Created The Nutcracker

In 1890, the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg premiered the ballet The Sleeping Beauty, which quickly became a success. This is why, a year later, in 1891, Ivan Alexandrovich Vsevolozhsky, director of the Imperial Theatres of St. Petersburg, proposed getting back together the creators of The Sleeping Beauty: Tchaikovsky, the composer, and Marius Petipa, the choreographer.

At that time, Russian ballet was the most prominent in the world. This flourishing was largely because of the state support from the Tsars. In this way, Russia became a meeting point for the greatest artists, choreographers, and dancers, both Russian and foreign. One of the great masters who worked in Russia was the talented French choreographer Marius Petipa (1818-1910).

Meanwhile, in other countries, such as France, ballet was in decline.

In 1881, Ivan Vsevolozhsky (1835–1909) was appointed director of the St. Petersburg theatres, a position he held until 1899. Vsevolozhsky was a painter and had worked at the Russian embassy in Paris. Unlike many of his predecessors, who accepted the position solely for the money, Vsevolozhsky was a cultured man, well-suited to the role. He loved music and ballet and contributed greatly to raising the standards of the Mariinsky. Some consider him a precursor to Sergei Diaghilev.

One of his first goals was to improve the quality of the ballet music. Since 1871, the official composer of ballet music for the Mariinsky had been the Viennese Ludwig Minkus. Although his music was rhythmic and very danceable, it wasn’t what Vsevolozhsky was looking for. So, in 1886, he secured Minkus a lifetime pension, leaving the position of composer vacant. Then Vsevolojsky, who admired Tchaikovsky, convinced Tsar Nicholas III in 1888 to grant the musician a lifetime pension.

You Might Also Like ✨

The Nutcracker Ballet Libretto

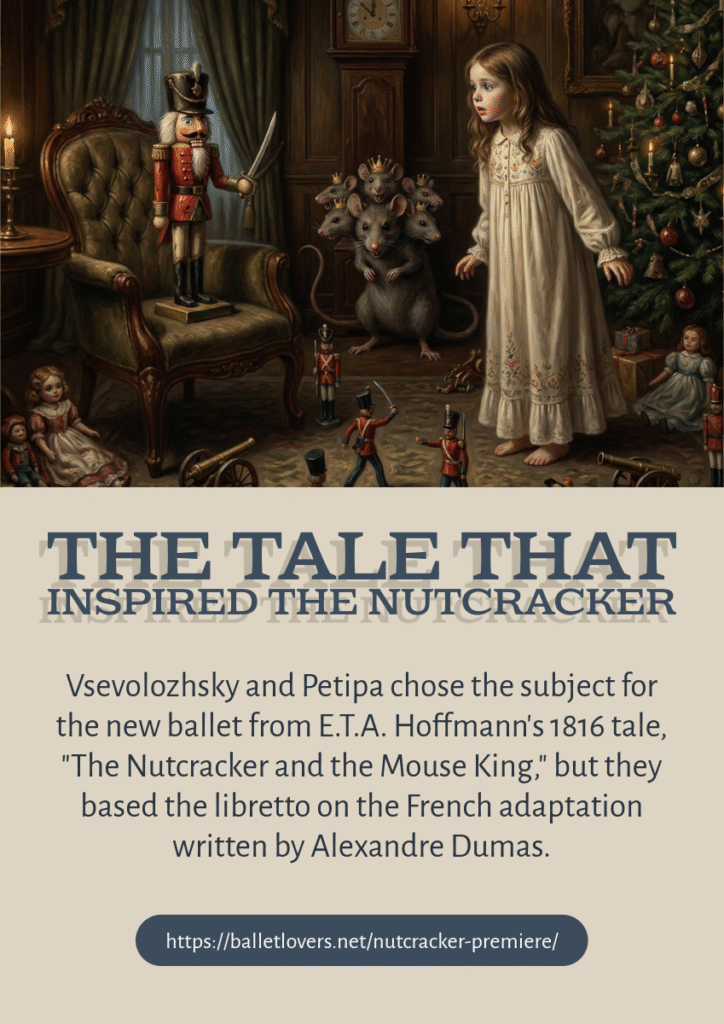

The subject of the new ballet was chosen from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s 1816 tale, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King,” which was very popular in Russia at the time. It achieved great popularity not only in German-speaking countries but also in other countries thanks to Alexandre Dumas père’s French adaptation, The Nutcracker of Nuremberg.

Hoffmann was very popular in the 19th century. His works served as inspiration not only for The Nutcracker but also for the ballet Coppélia and Offenbach’s opera The Tales of Hoffmann.

As with Sleeping Beauty, the idea of adapting the tale came from Ivan Vsevolozhsky, who was in charge of the imperial theatres at the time. During the writing of the libretto, in collaboration with Petipa, he made significant changes, as

anyone who reads Hoffmann will immediately notice. Both Vsevolozhsky and Petipa loved French culture. So they based it on Alexandre Dumas’ version, although they decided to simplify the story quite a bit.

So Vsevolozhsky commissioned Tchaikovsky to write a two-act ballet based on Hoffmann’s story. But Tchaikovsky didn’t show much enthusiasm. Tchaikovsky considered the score for The Sleeping Beauty his best work. On the contrary, he felt that the subject of The Nutcracker was far inferior to that of The Sleeping Beauty and disliked it. “The ballet is worthless compared with ‘The Sleeping Beauty’. This is clear as daylight to me” , he wrote in a letter to his nephew. Nevertheless, he gradually showed more interest in it. However, the composer had always dreamed of creating a ballet based on the old German fairy tale Ondine. But sadly, he could never fulfil his dream.

The Creation of The Nutcracker Score

The Nutcracker ballet belongs to the last and most tragic period of Tchaikovsky’s life and work. So he began working on the score in January 1891 without much enthusiasm. But little by little, he became interested. At the same time, he was also composing the opera Iolanta.

Tchaikovsky wrote The Nutcracker in record time. So, the composer began working on the music in mid-February 1891 and finished it on June 24 of that same year.

During the course of his work, in April 1891, one of the most tragic events in the musician’s life occurred: the death of his beloved sister. These profound emotions seem to have seeped into parts of the score. While still mourning his sister, he continued working on the second act.

This might explain why, at the end of what has always been called a decorative children’s ballet, we find the adagio music, so serious and challenging, of the grand pas de deux.

Musicologist Roland John Wiley has suggested that Tchaikovsky left a coded message in the rhythm of the adagio’s main melody, a descending scale of notes that is repeated “insistently, like a prayer”. This phrase bears a strong rhythmic resemblance to a verse from the Russian Orthodox funeral service. So, Wiley believed it could have been Tchaikovsky’s hidden tribute to his sister.

How Petipa and Tchaikovsky Worked Together

This brilliant score is arranged perfectly for the ballet’s action. This was achieved thanks to the close collaboration between the choreographer, Petipa, and the composer, Tchaikovsky. Petipa, a choreographer of vast experience, knew exactly what he wanted in terms of music and ensured that his composers delivered.

So, Petipa was a very meticulous choreographer, planning every possible detail of a ballet. He could begin choreographing a scene without music because, even before it was finished, he had an idea of what it would be like.

Whenever a composer agreed to write a score for him, Petipa would send them an outline of the action with detailed instructions about the type of music he wanted, measure by measure.

Although some composers disliked this way of working, Tchaikovsky had no problem doing so. Following Petipa’s instructions, he successfully composed the brilliant music for The Sleeping Beauty. So, Tchaikovsky and Petipa continued with the same working method for the ballet The Nutcracker.

For example, for the children’s entrance in Act I, Petipa requested loud and cheerful music from the composer. Towards the end of Act I, the fight between the Mice and the Soldiers is accompanied by music with a strong, fast rhythm. And in Act II, during the divertissements, the music is tailored to the nationality of each character (Spanish, Arabian, Chinese, and Russian dances).

Some of the melodies in this ballet, such as the Waltz of the Flowers, the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, and the March at the beginning of the first act, are among the most recognized works worldwide and frequently performed in the media during the Christmas season. Tchaikovsky created a special sound world in The Nutcracker with his orchestration, a ballet’s childlike atmosphere. So, Tchaikovsky paid close attention to instrumental effects.

The Celesta’s Debut in the Nutcracker Premiere

On one of his trips to Paris, the composer discovered an exotic instrument, the celesta, that would be perfect for the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy. It could be described as something similar to a piano, but with an angelic sound. The celesta (also known as celeste or bell-piano), is a struck idiophone operated by a keyboard. It looks like an upright piano (four- or five-octave), although with smaller keys and a much smaller cabinet, or a large wooden music box.

In one of his letters to Pyotr Ivanovich Jurgenson (his friend and principal publisher of his works), he wrote: “I have a request for you. I discovered a new orchestral instrument in Paris. This is something between a small piano and a glockenspiel, with a divinely wonderful sound…

It’s called the Celesta Mustek and costs 1200 francs. It can only be bought in Paris at the inventor Mustel’s shop. I would like to ask you to order this instrument for me”. Tchaikovsky asked Jurgensen to keep it a secret lest some of his rivals, particularly Rimsky-Korsakov, get wind of his intentions. He also wrote to Jurgensen:

“. . . have a thought that no one besides myself hears the sounds of this miraculous instrument before it is played in my works, where it will be used first … If the instrument comes first to Moscow, then keep it away from outsiders, and if to Petersburg], then have Osip Ivanovich [Jurgensen] watch over it“. So, the celesta was bought abroad and brought to Russia with full precautions.

Then, this instrument was first played in Russia at the premiere of The Nutcracker in 1892, during the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy. And in this way, the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy went down in history as the most famous melody ever where we can appreciate the sound of the wonderful celesta.

The Nutcracker Premiere

The Nutcracker Premiere at a Glance

- Ballet in two acts and three scenes

- Choreography: Lev Ivanov.

- Music: Petr Illich Tchaikovsky.

- Libretto: Ivan Vsevolozhsky and Marius Petipa, based on E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King.”

- Scenery: M.I. Botcharov

- First performance: 18 December 1892, Maryinsky Theater, Saint Petersburg.

- Principals: Stanislava Belinskaya (Clara), Sergei Legat (The Nutcracker), Antonietta Dell’Era (The Sugarplum Fairy), Pavel Gerdt (Prince Coqueluche), Timofei Stukolkin (Drosselmeyer).

On the eve of the ballet’s rehearsals, Petipa fell ill and had to leave the project. The production was entrusted to the Russian Lev Ivanov (1834-1901), the Mariinsky Theatre’s second choreographer and Petipa’s assistant. Ivanov was no novice. In a tribute to Tchaikovsky after his death, he was commissioned to choreograph part of a new version of Swan Lake. As Petipa’s assistant, he collaborated with the choreographer on several productions. So, he occasionally creating dances that would later be attributed to Petipa himself.

Despite these issues, The Nutcracker and Iolanta finally shared the bill and premiered on the scheduled date— first, the opera, and then The Nutcracker. As a result, the grand concert was very long and ended after midnight.

Designed by M. I. Botcharov and K. M. Ivanov, with costumes by Vsevolojsky, The Nutcracker starred the Italian ballerina Antoinette dell’Era as the Sugar Plum Fairy. Dell’Era’s partner was Pavel Gerdt, for years the most distinguished male dancer in Russian ballet.

The Nutcracker Premiere Critics

Although reviews of the ballet were varied, negative ones predominated. One of the most criticised aspects was the inclusion of a large number of children in the cast. Also, many theatregoers criticised the libretto of The Nutcracker. Hoffmann’s fans felt that the ballet had failed to capture the atmosphere of the story.

Among the audience was the Russian art critic and artist Alexandre Benois (1870-1960). He would collaborate with the famous Diaghilev Ballet years later. While Sleeping Beauty had fascinated him, The Nutcracker, on the contrary, disappointed him. According to Benois, “CasseNoisette has not turned out to be a success! And it was just in this ballet that I had placed all my hopes, knowing Tchaikovsky’s talent for creating a fairy-tale atmosphere….

The decor of Scene I is both disgusting and profoundly shocking… stupid, coarse, heavy, and dark… The second act is still worse… while at times the music reminds me of an open-air military band. Tchaikovsky has never written anything more banal than these numbers!”

However, over the years, Benois’s opinion of The Nutcracker changed. In 1892, the only parts of the work he liked were the Trépak, the tea and coffee dances, and the pas de deux. Most critics agreed with him regarding the pas de deux, with its majestic and flowing adagio and its delicate variation for the Sugar Plum Fairy. This pas de deux remains one of the few surviving fragments of Ivanov’s choreography for The Nutcracker. Most of Ivanov’s choreography has been lost over the years. What has endured is Tchaikovsky’s music. Although it may not have greatly impressed audiences at its premiere, has continued to gain popularity.

Conclusion

Despite the negative reviews, the ballet continued to be performed for the remainder of the 1892-1893 season. Although it disappeared from the stage for a time, it returned in the 20th century thanks to other choreographers who created new versions.

Finally, we would like to mention some words from the famous choreographer Yuri Grigorovich: “Without The Nutcracker, Stravinsky’s, Prokofiev’s and Shostakovich’s ballet scores would have been impossible. This masterpiece of art stimulated a quest of new styles and forms in the sphere of choreography.”

Bibliography

- Maynard, Olga. The Ballet Companion: An Illustrated How to Look and How to Listen Guide to Four of the Most Popular Ballets in the Modern Repertoire, and the Great Ballet Companies That Perform Them.

- Beaumont, Cyril W. Complete Book of Ballets. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

- Searle, Humphrey. Ballet Music: An Introduction. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Wiley, Roland John. Tchaikovsky’s Ballets: Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, Nutcracker. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grigorovich, Yuri; Demidov, Aleksandr; Pchalkin, Vladimir; Axelrod, Herbert R. The Official Bolshoi Ballet Book of The Nutcracker.

- Anderson, Jack. The Nutcracker Ballet.

- Fisher, Jennifer. Nutcracker Nation.

Leave a Reply