Is Ivanov’s Nutcracker version the only one that exists? Are all Nutcrackers the same? No, after the premiere of The Nutcracker in 1892, other choreographers decided to create their own versions of this beautiful ballet.

Among those who staged notable productions of The Nutcracker in Russia were Aleksandr Gorsky, Fedor Lopukhoy, Vasily Vainonen, and Yuri Grigorovich. In this article, we tell you in detail about each of these versions.

Table of Contents

Gorsky’s Version of The Nutcracker (1919)

In the 20th century, the first choreographer to create a new version of The Nutcracker was Alexander Gorsky (1871-1924), a Russian dancer, choreographer, and teacher. Gorsky danced with the Maryinsky Theatre company in St. Petersburg from 1889 to 1900 and participated in Petipa’s ballets. One of the roles he performed was that of the Chinese Dance in The Nutcracker.

Later, at the beginning of the 20th century, he moved to Moscow, where he directed the Bolshoi Ballet for about twenty years. During his time at this theatre, Gorsky completely revamped its repertoire, creating new ballets and revising old ones. He went down in history as a reformer of the strict academic style of dance.

You Might Also Like ✨

Innovations in Gorsky’s Nutcracker

Among the revisions, The Nutcracker, which premiered at the Bolshoi in 1919, stands out. Gorsky heightened the elements of fairy-tale fantasy. One of the changes involved reorganising the musical numbers into a three-act production instead of the two acts of the original version. Another change was the addition of a new character, Drosselmeyer’s wife, who was courted by young men. Also, Gorsky isolated the “Waltz of the Snowflakes” in a separate act, to which he transferred the grand pas de deux from the original second act.

The rest of the ballet was conceived as a child’s dream. It began with the protagonist tracing drawings on a frosted window with her finger. The window disappeared to give way to the dance of the snowflakes.

It’s important to remember that between 1918 and 1921, Russia was experiencing a civil war. Then, in 1919, there was no tarlatan, the fabric usually used to make tutus. So, the artist and designer Konstantin Korovin (1861-1939) was forced to dress the snowflakes in imitation Russian fur coats, with muffs in their hands. These snowflakes danced before Santa Claus.

Gorsky’s Nutcracker was not preserved. However, he started the tradition of giving the great adagio of the Sugar Plum Fairy

and Prince Koklush to Clara and the Nutcracker Prince. This tradition has been used in all

other Soviet productions, especially in Vasily Vainonen’s most performed version from 1934.

KEY INFO

Tarlatan is a stiff, lightweight, open-weave cotton fabric widely used in classical ballet tutus, especially in the pancake tutu, where multiple layers create stiffness and hold the flat shape.

Lopukhov’s Version of The Nutcracker (1929)

The Mariinsky Ballet’s repertoire is striking for its breadth and diversity. It not only includes great classical works but also stands out for its innovation and bold experiments. So, after the 1917 Revolution, the company actively looked for contemporary composers and themes. Also, in this context, the theatre made great efforts to preserve some of its major productions. But by 1923, the situation at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg was far from easy. Many of its talented dancers, who did not support the 1917 revolution, had gone into exile. Besides, state financial assistance was no longer an option.

On the other hand, the veteran ballet master Marius Petipa had been dismissed from his post fourteen years before the Revolution.

And no one had emerged as his successor. The Revolution sparked intense questioning of the ballet’s right to exist, with many claiming it was obsolete. But when ballet reasserted its position as a symbol of Russian culture, Fedor Vasilevich Lopukhov (1886-1973) became Petipa’s heir. In this way, Lopukhov was appointed artistic director of the Mariinsky, which would later be known as the Kirov Theatre of Leningrad.

Fedor Lopukhov: The Restorer & Innovator of Classical Ballet

Lopukhov wasn’t a great dancer, but he was an excellent choreographer and teacher.One of his most outstanding merits was preserving almost the entire classical repertoire by meticulously restoring them. When the original was forgotten, Lopukhov replaced the old choreography with a new version of his own creation. What is surprising, however, is that no expert could distinguish, in Petipa’s old versions, where the choreography was his and where it was later created by Lopukhov. Lopukhov was so familiar with the style of the old masters and so masterfully commanded the choreographic styles of different eras that, in restoring the old ballets, he ingeniously “faked” the originals.

But Lopukhov also dedicated himself to experimenting with new forms of choreographic art.

So, he became a leading figure among modern choreographers in Leningrad in the early 1920s. During his years with the Kirov Ballet, Lopukhov tried to instill an innovative spirit in the company, creating his own interpretations of ballet classics. In this way, Lopukhov introduced acrobatic elements into ballet. So, he combined classical dance with new movements, whether borrowed from sports or acrobatics, or completely new steps he invented.

Lopukhov’s Controversial Nutcracker

One of Lopukhov’s creations was his controversial version of The Nutcracker, presented at the Kirov Theatre in 1929. In the case of The Nutcracker, Lopukhov disliked Ivanov’s version. So he revised much of the choreography, including the Waltz of the Snowflakes. Lopukhov wrote: “The ‘Snowflakes’ scene lacks harmony and growth and is incorrectly developed in terms of musical themes. The figures changing after every eight bars cannot be used throughout the ‘Waltz of the Snowflakes.’ No attention is paid to the theme of the chorus singing in the wings.” For this reason, in the revival of The Nutcracker, the choreographer was clearly freer in his interpretation than on other occasions.

Lopukhov created this new version of The Nutcracker as a social satire.

He presented it as a revue of 22 episodes satirising the characters of Imperial Russia. Among the characters were a general with epaulettes, a tsar and tsarina who were the heroine’s parents, a civil servant with a briefcase, a lady-in-waiting, and other vestiges of Tsarist Russia. Lopukhov arbitrarily mixed episodes from the fairy tale with contemporary elements. Also, he used a recitation of Hoffmann’s text to accompany the dances.

In the final waltz, the dancers rode bicycles. In the pas de deux, the heroine was carried upside down in an inverted grand écart (split).

Her adagio consisted of a series of acrobatic feats. The snowflakes dressed as ballerinas and performed somersaults. The Nutcracker, ill, hobbled across the stage on crutches and, in a panic, packed his suitcases to escape the Mouse King. And the heroine’s wedding dress was made from the fur of a defeated mouse.

KEY INFO

The Revue was a very popular format at that time. It was a light theatrical entertainment consisting of a series of short sketches, songs, and dances, typically dealing satirically with topical issues.

Conclusion

But his work was not well received. The new version enraged both conservatives and innovators and was removed from the repertoire immediately after its premiere. The impact of this production was so strong that The Nutcracker disappeared from ballet stages for five years.

However, despite the controversy, Lopukhov’s version introduced elements that became standard in later productions. For example, Lopukhov renamed the role of Clara to Masha, which is a Russian diminutive of Marie. On the other hand, the pas de deux of the second act was performed by the protagonists (Masha and the Nutcracker Prince), instead of the Sugar Plum Fairy and her knight(Prince Koklush).

KEY INFO

It’s worth remembering that “Kirov” was the name given to the Mariinsky Theatre during the Soviet period (1935-1992), in honour of the Soviet politician Sergei Kirov. Meanwhile, during this same period, the city of St. Petersburg was renamed Leningrad, in honour of Vladimir Lenin.

Vainonen’s Version of The Nutcracker (1934)

Vasily Vainonen (1901-1964) was a Russian dancer and choreographer who graduated from the Mariinsky Theatre School in 1919. In the early 1920s, Vainonen came into contact with the Young Ballet (Molodoi Balet in Russian), an avant-garde dance group founded by the renowned George Balanchine.

This marked the beginning of Vainonen’s career as a choreographer, as he created several dances for this young group. Gradually, Vainonen abandoned dance altogether and devoted himself entirely to choreography. His first ballet, The Golden Age, with music by Shostakovich, premiered at the Kirov Theatre in 1930.

KEY INFO

Avant-garde means in French ‘advance guard’ or ‘vanguard’. So, in the case of ballet, it’s a group of dancers, choreographers, and/or artists who look for breaking with the traditions of classical ballet and experiment with new languages of movement, themes, and stage aesthetics.

Vainonen’s The Nutcracker: A Version Still Performed at the Mariinsky Theatre

But one of his most renowned works is undoubtedly his revision of The Nutcracker, presented at the Kirov Theatre in 1934. Instead of making his first-act heroine a seven-year-old girl, he made Masha a teenager. This meant an adult ballerina could perform the role. In the first act, Masha receives a ballerina doll, a jack-in-the-box, and a wooden doll. She decides the doll is her favourite Christmas present. It is he who saves her from the mice, after which he transforms into a handsome prince. And it is this same prince with whom she dances the pas de deux usually assigned to the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Prince.

Vainonen’s version of The Nutcracker is an important early attempt to make Clara and the Sugar Plum Fairy essentially the same.

Other productions by other choreographers have continued to make the same identification. Also, Vainonen’s version is one in which, despite the title, the nutcracker has little or no importance. The most prominent scene was the Waltz of the Snowflakes, probably a modernized version of Ivanov’s masterpiece.

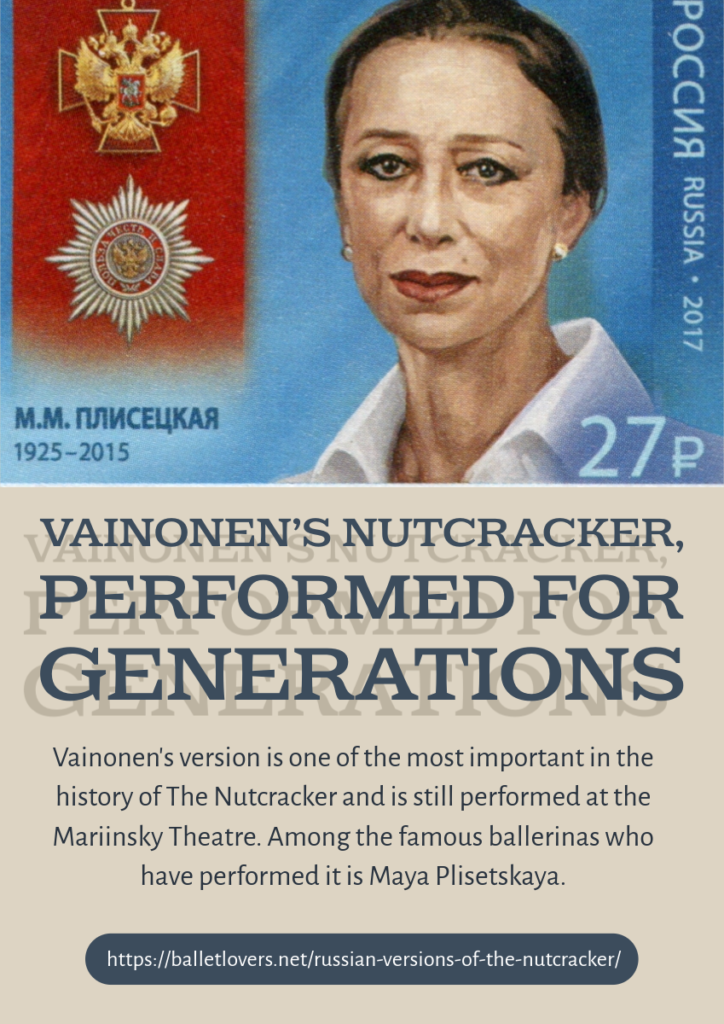

Years later, in 1939, Vainonen premiered The Nutcracker at the Bolshoi. This version was virtually the same as the one he had premiered a few years earlier at the Kirov. On the other hand, Vainonen’s Nutcracker remained the only acceptable version of the ballet for over thirty years. It was part of the repertoire of the leading Soviet ballet companies and the Mariinsky Theatre continues to stage it today. Two great Russian ballerinas became famous for their interpretations of Masha: Galina Ulanova, at the premiere, and in a revival several seasons later, Maya Plisetskaya.

Grigorovich’s Version of The Nutcracker (1966)

The Russian Yuri Grigorovich (1927-2025) graduated from the Leningrad Ballet School in 1946. From a young age, he showed a preference for choreography. So, while still in school, he began choreographing short pieces. Later, classical ballets occupied an essential place in Grigorovich’s repertoire. He created new versions of all of Tchaikovsky’s ballets, including The Nutcracker.

The Nutcracker marked the beginning of a new stage in Grigorovich’s professional life. It was his first original production at the Bolshoi after being appointed chief choreographer in 1964. Below, Yuri Grigorovich expresses his opinion about this ballet:

“Was it true that it was simply unfit for the stage, as it was claimed by some authorities on ballet? Some traced these setbacks to mistakes on the stage, others to the choreographers’ insensitiveness to the music or insufficient attention to the literary source.”

At first I presume that the scenario really needed a radical revision and that the music should also be re-examined from the point of view of the dramaturgy brought into line with the Hoffmann story.

“A careful study of the score, however, convinced me that Hoffmann and Tchaikovsky had in fact produced very different works, and the link between them was based on their inner affinity.

“What then would be the point of departure in my own version: the music, the tale, or my own ideas? (…)

“I wholly entrusted myself to Tchaikovsky’s score. That was why I said in an interview after the premiere: ‘I simply listened to the music and followed its guidelines.’ (…)

“I realized that a choreographer determined to come up with his own version of The Nutcracker is obliged to abandon any preconceived notions and heed the voice of his own instinct.”

The Premiere of The Nutcracker at the Bolshoi in 1966

In this way, Yuri Grigorovich presented his version of The Nutcracker for the Bolshoi Ballet of Moscow on March 12, 1966. Since then, it has become an essential work of the Bolshoi and one of its most popular and well-known ballets. Also, the Bolshoi Company presented this ballet in the United States, Great Britain, France, Italy, and other countries.

The premiere starred the brilliant dancers Ekaterina Maximova as Masha and Vladimir Vasilyev as the Prince. Afterwards, virtually all the principal dancers of the Bolshoi Ballet joined the cast of The Nutcracker. For example, Yuri Vladimirov and Vyacheslav Gordeyev as the Prince, and Lyudmila Semenyaka and Nadezhda Pavlovas as Masha.

In this work, Grigorovich returned to the two-act version and completely restored Tchaikovsky’s original score. No children participated in this new version. Adult dancers performed the roles of Masha’s friends, her brother, and his friends.

Set designer Simon Virsaladze (1909-1989) created the image of a constantly changing Christmas tree, which extended throughout the entire production. So, Grigorovich succeeded in creating a ballet for adult audiences without altering its fantastical character.

In conclusion, The Nutcracker took almost seventy-five years to become established on the stages of Russian ballet. Grigorovich’s production returned the ballet to its origins. Also, it marked the beginning of the modern history of the Bolshoi Ballet with its brilliant achievements under his innovative direction. To this day, the Bolshoi continues to perform Grigorovich’s version.

Bibliography

- International Encyclopedia of Dance. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Morrison, Simon. Bolshoi Confidential: Secrets of the Russian Ballet from the Rule of the Tsars to Today. New York: Liveright, 2016.

- Haskell, Arnold L. The Russian Genius in Ballet: A Study in Continuity and Growth. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1935.

- Grigorovich, Yuri; Demidov, Aleksandr; Pchalkin, Vladimir; Axelrod, Herbert R. The Official Bolshoi Ballet Book of The Nutcracker. Moscow: Bolshoi Theatre Press, 1990.

- Gregory, John, and Alexander Ukladnikov. Leningrad’s Ballet: From the Mariinsky to the Kirov. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1983.

- Roslavleva, Natalia Petrovna. The Era of the Russian Ballet. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1966.

- Clarke, Mary. Ballet: An Illustrated History. London: Hamlyn, 1981.

- Chujoy, Anatole, ed. The Dance Encyclopedia. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1949.

- Souritz, Elizabeth. Soviet Choreographers in the 1920s. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1989.

- Pokrovsky, Boris. The Bolshoi: Opera and Ballet at the Greatest Theater in Russia. Moscow: Raduga Publishers, 1989.

- Anderson, Jack. The Nutcracker Ballet. New York: Dance Horizons, 1981.

Leave a Reply