The ballet Sylvia, also known as “Sylvia ou la Nymphe de Diane,” is a fundamental work in the history of classical ballet, fusing mythology, romance, and heroism. This ballet was created in 1876 for the Paris Opera, with choreography by Louis Mérante and a brilliant score by Léo Delibes. Sylvia, originally presented in three acts, is based on Torquato Tasso’s poem Aminta.

It tells the story of the nymph Sylvia, devoted to the goddess Diana, who rejects the love of the shepherd Aminta.

For nearly 150 years, Sylvia has inspired numerous choreographers worldwide. From the original production starring Rita Sangalli to versions by Ivanov, Lifar, and others, the ballet has been reinvented many times. However, the most influential modern version is Frederick Ashton’s revival for the Royal Ballet in 1952. In this article, we tell you all about the most popular versions of this ballet, as well as its plot and the importance of Delibes’ music.

Table of Contents

The Plot of Sylvia – A Detailed Summary

This ballet unfolds in a mythical world where gods, nymphs, and mortals intertwine in a tale of forbidden love.

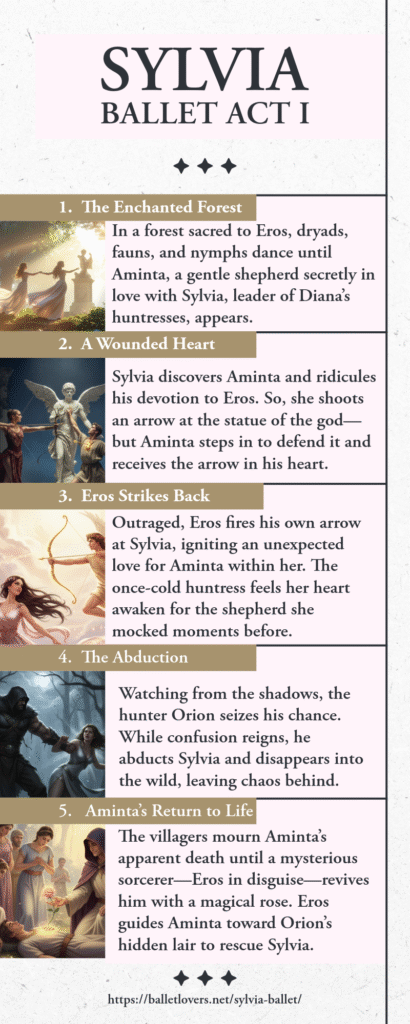

Act I: The Sacred Wood

The story opens in a mythical forest dedicated to the god Eros. The forest spirits—dryads, fauns, nymphs—dance joyfully until they disperse at the arrival of Aminta, a shepherd secretly in love with Sylvia, leader of the huntresses of the goddess Diana. Aminta, for his part, is devoted to the god Eros.

Suddenly, Sylvia discovers the shepherd and mocks his devotion to the god. So, she shoots an arrow to destroy the statue of Eros.

But Aminta steps in to protect the statue, taking the arrow to his heart. Then, Eros decides to take revenge, shooting his own arrow at Sylvia and awakening in her love for Aminta.

Meanwhile, the dark hunter Orion, who has been observing the scene, seizes the opportunity to abduct Sylvia. The peasants mourn Aminta’s apparent death until a mysterious sorcerer—who turns out to be Eros in disguise—revives him with a magic rose.

Eros encourages Aminta to rescue Silvia, showing him the way to Orion’s lair.

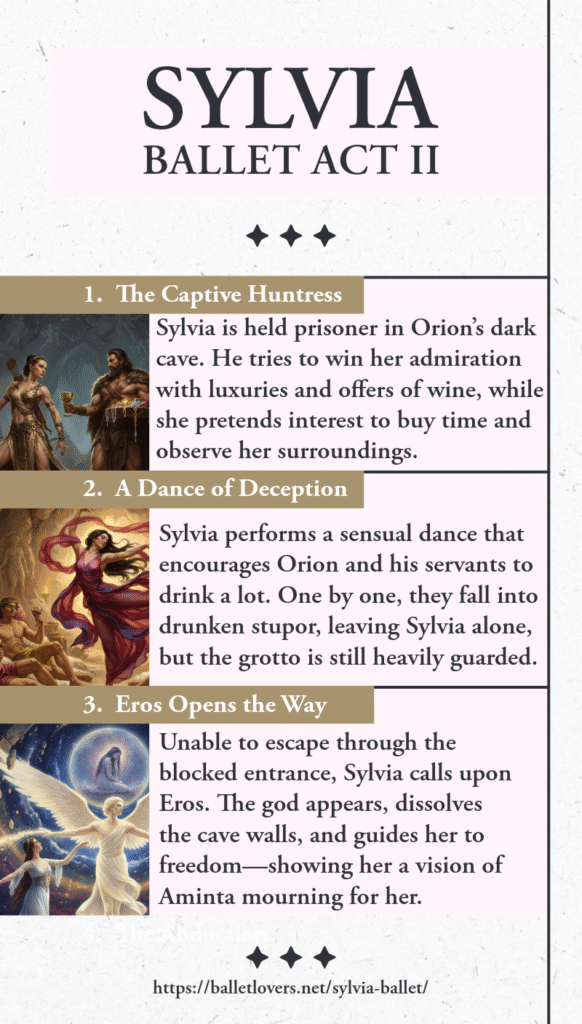

Act II – Orion’s Grotto

The second act moves to Orion’s rocky grotto, where Sylvia is being held captive. She resists his advances, simulating interest to buy time.

Orion offers her luxuries and wine, and Sylvia cleverly performs a seductive dance inspired by Bacchus.

This encourages him to drink to excess until he and his slaves succumb to drunkenness. However, finding herself unable to escape the guarded entrance, Silvia begs Eros.

The god appears, the walls of the grotto vanish, and he leads her to freedom. As she flees, Eros shows her a vision of grieving Aminta.

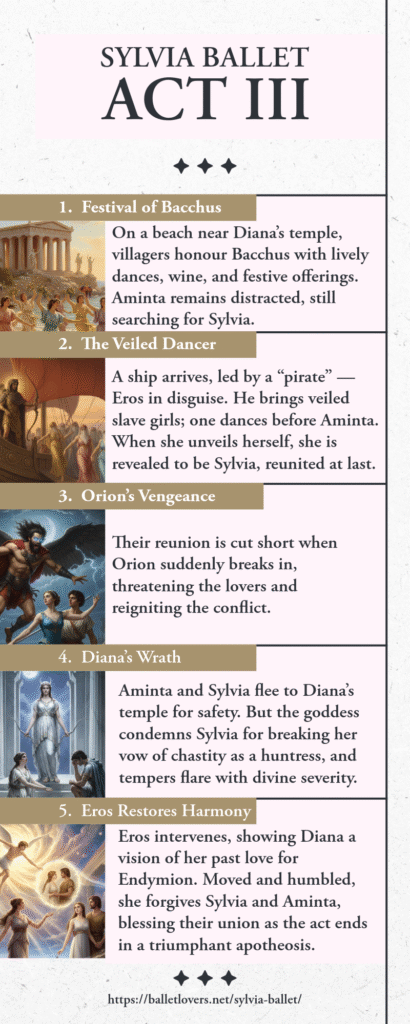

Act III: The Temple of Diana

In the third act, on a beach near the temple of Diana, the villagers celebrate a festival in honour of Bacchus with dances and offerings. Aminta, still preoccupied with the search for Sylvia, is overjoyed to see a ship arrive, captained by a “pirate” (Eros in disguise), bringing slave girls with their faces covered by veils.

One of them dances before Aminta and, upon removing her veil, reveals herself to be Sylvia. Their reunion is short-lived, as Orion bursts onto the scene.

Then, the lovers seek refuge in the temple of Diana. But Sylvia is forbidden to love because she belongs to the band of Diana’s Huntresses.

So, the goddess, enraged, condemns Sylvia for breaking her vow of chastity by loving a mortal. At that moment, the god Eros intervenes, evoking a vision of Diana’s past romance with the shepherd Endymion.

Ashamed by the memory, Diana forgives the lovers and blesses their union in the middle of triumphant festivities and a grand apotheosis.

The Original Version and Première

SYLVIA AT A GLANCE

- Ballet in three acts.

- Choreography by Louis Mérante.

- Music by Léo Delibes.

- Libretto by Jules Barbier and Baron de Reinach (after Torquato Tasso’s Aminta).

- Scenery by Jules Chéret, Alfred Rubé, and Philippe M. Chaperon.

- Costumes by Eugène Lacoste.

- First production: Paris Opéra, June 14, 1876.

- Principal dancers: Rita Sangalli (Sylvia), Louis Mérante (Aminta), Marco Magri (Orione), Marie Sanlaville (Eros), Louise Marquet (Diana).

The premiere of Sylvia took place at the Paris Opera on June 14, 1876, with choreography by Louis Mérante (1828-1887) and the Italian ballerina Rita Sangalli (1849-1909) in the title role.

According to ballet historians, the French composer Léo Delibes (1836-1891) worked closely with Mérante and Sangalli from the very first rehearsals.

Many numbers were rewritten several times to adapt them to the choreographic needs and to highlight the ballerina’s virtuosity. Also, Louis Mérante danced the role of Aminta.

On the other hand, the plot was based on a libretto by Jules Barbier and Baron de Reinach, adapting the pastoral drama Aminta by the Italian poet Torquato Tasso (1544-1595). This adaptation followed the tradition of mythological themes that were fashionable in French ballet at the time.

The set design, by Jules Chéret, Alfred Rubé, and Philippe Chaperon, featured lush forests and grottoes, while Eugène Lacoste designed the costumes, emphasizing a mythological style.

Despite its complexity, this production is often considered a landmark in the period of decline of creative choreography at the Paris Opera in the late 19th century.

While the ballet dazzled audiences with its grand staging, critics considered the plot weak and the choreography lacking in drama.

However, its score was immediately recognized as a masterpiece. Contemporary critics praised Delibes for its originality, richness, and ingenious orchestration. Despite the excellent score, the original production disappeared from the repertoire.

Later Versions and Revivals

Throughout the 20th century, several choreographers attempted to revive Sylvia, captivated by Delibes’s radiant score. However, most of the early revivals failed to achieve lasting success. Below are some of the most notable versions:

- Giorgio Saracco (La Scala, 1896) – based on Mérante’s version and performed by the dancer Carlotta Brianza.

- Lev Ivanov and Pavel Gerdt (Mariinsky Theatre, 1901) with Olga Preobrajenska as Sylvia.

- Fred Farren (London, 1911) – a one-act version with re-orchestrated music and starring Lydia Kyasht.

- Serge Lifar (Paris Opera, 1941)

- Albert Aveline (Paris Opera, 1946)

- John Neumeier (Paris Opera, 1997)

However, the two most influential versions in the modern repertoire are those of George Balanchine (1950) and Frederick Ashton (1952).

Sylvia Ballet – Opéra National de Paris – Choreographer: John Neumeier

Balanchine’s Sylvia Pas de Deux (1950)

Of course, we must mention Balanchine’s version. The prestigious choreographer George Balanchine (1904-1893) admired Delibes. So, he decided to recreate this ballet in his own way, creating a Pas de Deux for Sylvia. While not a complete staging of the ballet, his pas de deux became an emblematic piece, highly representative of the Romantic era.

This classic pas de deux was created especially to showcase the virtuosity of Maria Tallchief. Its entrance, adagio, solos, and coda contain a wide variety of brilliant and exceptionally difficult actions for both the ballerina and the principal dancer. The ballerina, for example, must perform entrechatshuits, turns in the air (tours en l’air), landing on her toes, fast pirouettes, and extended leaps on one pointe across the stage. The music for the ballerina’s solo is the well-known “Pizzicato Polka” by Léo Delibes.

This ballet remains part of the New York City Ballet’s repertoire and is one of Balanchine’s most elegant small-scale works inspired by 19th-century music. On the other hand, this pas de deux is frequently performed in galas and mixed programs.

Frederick Ashton’s Sylvia (1952) — A Masterpiece Reborn

KEY INFO

- Choreography by Frederick Ashton.

- London, Covent Garden, September 3, 1952.

- Principal Dancers: Margot Fonteyn, Michael Somes.

The British choreographer Frederick Ashton (1904-1988) first considered creating a new version of Sylvia in 1947, exploring Léo Delibes’s score as a possible subject for his first three-act ballet. At that time, he consulted ballet critic Richard Buckle (1916-2001), who suggested relocating the plot to the Second Empire (the period in France under Napoleon III, from 1852 to 1870). Buckle proposed that “Sylvia, instead of being a nymph of Diana, would become Lady-in-Waiting to the Empress,” with Aminta transformed into the Duc de Marseille (Duke of Marseille), mistakenly identified as a gamekeeper, and Orion reimagined as “an amorous Baron.” The entire action would unfold as if the characters were preparing a masquerade for the Empress’s entertainment, lending it a “vague poetic atmosphere.” At the beginning, Ashton accepted this idea and asked Buckle to contact the designer Jean Hugo.

But he ultimately abandoned the project and opted for the ballet Cinderella.

On the other hand, Ashton also discussed the project with the popular art critic Sacheverell Sitwell (1897-1988). So, he advised Ashton via letter to simplify the plot. Sitwell, who had seen Sylvia Ballet in Paris, explained that he had mostly forgotten the ballet’s action, only recalling the music. So, he believed that the story should be made as simple as possible so that the entire focus could be on the music and the dancing. Ultimately, Sitwell expressed his confidence that Ashton could create something beautiful with the score.

Decision to Produce the Ballet (1952)

Finally, after months away from his company, Ashton returned and committed to working on his version of Sylvia. The work was announced for the end of the season and premiered on September 3, 1952, at Covent Garden. Ashton followed the original 1876 libretto by Jules Barbier and Baron de Reinach quite closely, and also consulted Tasso’s poem.

In the original plot, Sylvia, a nymph of Diana who has sworn chastity, rejects the shepherd Aminta. Eros makes her fall in love, but she is kidnapped by the hunter Orion. After Eros rescues her, Diana forbids the union until Eros reminds her of her own mortal love, Endymion. Finally, Diana blesses the lovers’ union.

Ashton decided not to parody the music or the plot, introducing humor solely through Eros.

As he explained: “In the first act… there is supposed to come on quite seriously a sorcerer to that very silly tune… I thought… I’ll make that slightly comic… in mythology the God of Love is always up to pranks.”

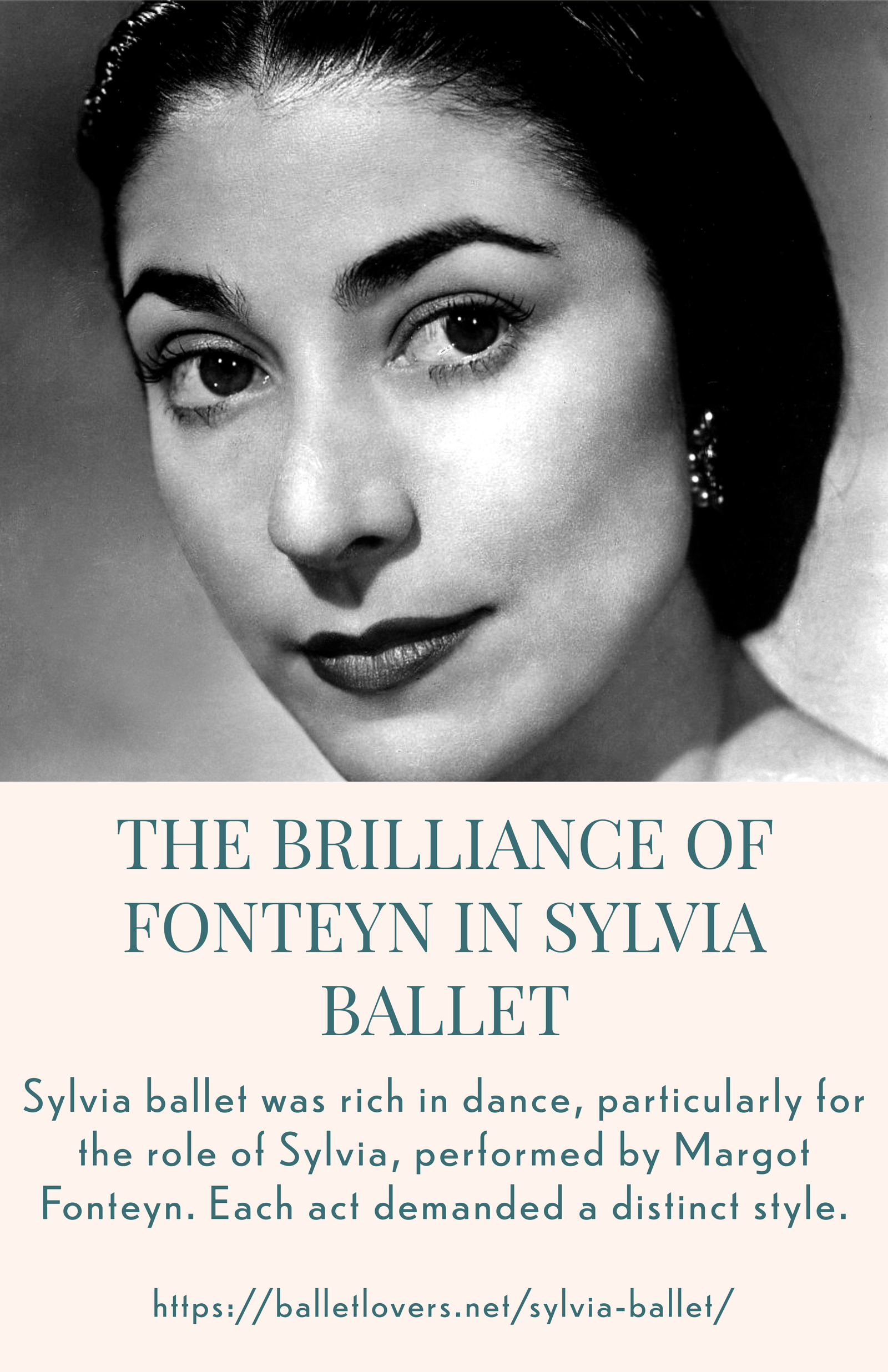

The ballet was rich in dance, particularly for the role of Sylvia, performed by Margot Fonteyn. Each act demanded a distinct style:

- Act I: a distant Amazon huntress.

- Act II: resisting Orion, and then feigning seduction.

- Act III: a completely classical ballerina, culminating in the pizzicati variation and the pas de deux with Michael Somes.

Musical Structure

Ashton had never seen any version of the ballet Sylvia. So, he decided to go to Paris to see the French version. But he ultimately changed his mind, not wanting to be influenced by another choreographer. Working with the conductor and musical director Robert Irving, he rearranged musical numbers and inserted four pieces from La Source (Delibes’s first ballet) into the third act to compensate for what he felt was a lack of drama in Delibes’s final act.

Ashton’s sensitivity to 19th-century ballet music guided his movement style. According to Ashton, “Hearing this 19th-century music, it’s impossible for me… to depart from the spirit of the music.” According to a dream he later recounted, Delibes himself appeared to him and said, “Vous avez sauvé mon ballet.” (You have saved my ballet.)

Critical Reception

Initial reviews in Great Britain were not the best. However, the pas de deux in the final act was highly praised. The prestigious dance critic P.W. Manchester remarked that Ashton always treated the pas de deux as a love scene. He specifically highlighted the tender moment when Aminta drew Sylvia’s head back against his cheek. On the other hand, American critics were much more complimentary the following year.

Regarding the score, critics noted Delibes’s innovative contribution to ballet music, moving it beyond the “tinkle-tinkle melodies,” according to American critic Carl Van Vechten. Ashton sought to honor both Delibes and Mérante.

Revisions and Structural Changes

Later, Ashton introduced key improvements, such as replacing a pictorial vision of Diana and Endymion with a tableau vivant (living tableau). After 1956, he incorporated some acrobatic elements into the choreography, influenced by the Bolshoi.

Finally, Ashton also created a shorter, one-act version, which premiered in 1967.

However, years later, a new chapter would be added to the story of Ashton’s Sylvia version. In 2004, Christopher Newton, who had worked as a ballet master under Ashton, was commissioned to reconstruct the ballet Sylvia for the Royal Ballet.

Since Ashton never notated his choreography, Newton relied on film footage, photographs, and his own memory to reconstruct Sylvia in its complete original form.

While modern productions sometimes adjust the structure of the performance, the choreography is based on Ashton’s full three-act design from 1952, and not on the abridged one-act version he created in 1967. In conclusion, the version presented today, both in London and in American revivals, reflects Ashton’s original conception.

KEY INFO

A tableau vivant (French for “living picture”) in the context of ballet or theatre is a technique where one or more actors or dancers pose silently and motionlessly, creating a static, arranged scene. In Frederick Ashton’s version of the Sylvia ballet, he originally had a painted vision of Diana and Endymion shown on stage. He later replaced this with a tableau vivant to make the scene far more satisfactory, meaning dancers posed to embody the moment instead of having a painted image serve the purpose.

Conclusion

As critics noted at the time, Ashton’s Sylvia was acclaimed for elevating ballet from obscurity to artistic triumph. Many critics considered it one of Ashton’s greatest achievements and a model of musical interpretation in ballet. Today, Ashton’s version is considered the definitive Sylvia of the 20th century.

Léo Delibes’ Score — The Heart of Sylvia

Although Sylvia’s original choreography was considered bland, the reason this ballet has survived to the present day is precisely thanks to Léo Delibes’s score.

Many historians describe it as a masterpiece of 19th-century ballet music and consider Delibes “the father of modern ballet music.”

The composer introduced several innovations to ballet music composition. For example, the use of leitmotifs (recurring musical ideas) and a symphonic structure, unusual for his time.

Movements such as Pizzicato, Valse Lente, and the hunting themes from Act I achieved great fame beyond the ballet stage, often being performed independently in concert halls.

Delibes’s achievement was revolutionary. As art historians point out, before his work, ballet music was usually little more than “tinkling melodies” with simple rhythms. With Sylvia, Delibes established a new artistic standard that redefined the future of ballet music and influenced great masters such as Tchaikovsky.

Buy your tickets for Sylvia Ballet 2026

American Ballet (ABT on Tour)

- Costa Mesa, California (Segerstrom Center for the Arts): April 9 – 12, 2026

Houston Ballet

- February 26 – March 8, 2026

Bibliography / Sources Consulted

- Terry, Walter. Ballet Guide. New York: Popular Library, 1977.

- The Simon and Schuster Book of the Ballet. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980.

- Beaumont, Cyril W. Complete Book of Ballets. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1938.

- Clarke, Mary. Encyclopedia of Dance and Ballet.

- International Dictionary of Ballet. Detroit: St. James Press, 1993.

- Balanchine, George, and Francis Mason. Balanchine’s Complete Stories of the Great Ballets. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977.

- Vaughan, David. Frederick Ashton and His Ballets. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977.

- Buckle, Richard. Buckle at the Ballet. New York: Atheneum, 1980.

Leave a Reply